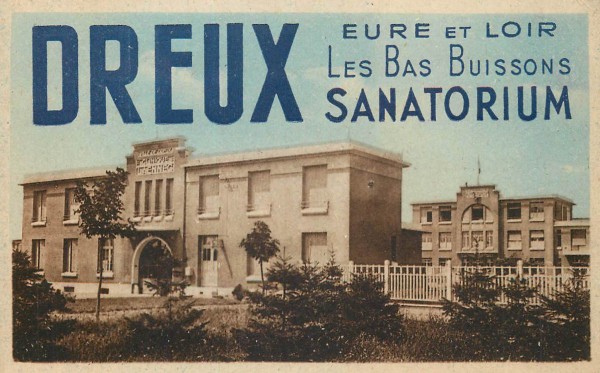

Urban exploration - The Dreux sanatorium

This report covers the Dreux Sanatorium, known locally as the Bas Buissons Sanatorium. It is a massive complex consisting of eight buildings spread across some 40 hectares. The architectural site is located northwest of Dreux in the hamlet of Les Buissons. This documentary is presented as a record of civil heritage, though one might wonder how that is even conceivable given how dilapidated the premises have become under constant, relentless layers of vandalism. Still, there is at least one advantage: for once, the damage is not directed at major historical heritage (as is the case in Lanaye, for instance, where 15th-century inscriptions were defaced with spray paint). We shall pass over the presence of various ghosts—including a 14-year-old girl whose soul supposedly wanders the "haunted" halls—even though many go to great lengths to prove this is the most haunted place in France.

During the First World War, tuberculosis wreaked havoc as an extremely contagious disease. Soldiers on the front lines were particularly affected due to overcrowding and the miserable conditions they endured. After the war, a multitude of sanatoriums flourished to treat the illness, alongside preventoriums designed for those with milder forms of the disease.

The Dreux Sanatorium was hastily built in 1928 under the leadership of Mayor Maurice Viollette. Fully operational by 1932, the site was intended to combat the spread of tuberculosis in the Dreux region. In 1935, the site was expanded with a convalescent home for women. At its peak during those years, the facility had a capacity for approximately 1,000 people, though that figure was never actually reached. Indeed, by 1940, the building was operating at only a third of its capacity and was gradually decommissioned starting in 1956. Medical progress was inevitably the cause; the building logically became obsolete over time.

During the Second World War, it served as a military hospital run by the US Army. In the 1960s, once tuberculosis had been eradicated, the buildings lingered on, being used as a retirement home and later as a medico-pedagogical institute from 1962 to 1980. The site finally closed its doors for good in 1990. In 1999, with the site completely abandoned, the city of Dreux bought back the land and its painful legacy for a symbolic franc.

The architects of this vast project were Georges Beauniée and André Sarrut.

André Sarrut, originally from Béthune and employed as an architect in a Paris firm, won the architectural competition for the sanatorium's construction. According to Sarrut’s son: "The mayor, who was a prudent man, thought: 'André Sarrut is young, I will pair him with the architect I trust, Georges Beauniée.' He took André Sarrut under his wing and eventually sold him his firm." This explains why two architects worked on the project. Notably, the sanatorium launched a long career for Sarrut in Dreux, where he served as the city architect between 1930 and 1965.

Architecturally, the site is divided into several sections:

-

A preventorium, named Thérèse Viollette, opened in 1931 with a 300-bed capacity.

-

A sanatorium, named the Laennec Clinic, opened in 1932 with a 400-bed capacity.

-

A rest home, opened in 1935 with a 50-bed capacity.

-

A geriatric center, built in 1939 but never opened due to the Second World War.

The center included a theater and several recreational areas to help patients through their long treatments, as time inevitably dragged on. Teachers who were themselves afflicted with the disease taught the children on-site. The sanatorium functioned as a closed community with significant autonomy and very strict rules.

Children and adults could remain there for several years. There is no denying that it was primarily a measure of isolation, bordering on incarceration. While patients were treated (mainly through sun therapy), it was, in many ways, a place where people went to die. At the very beginning, the site was at the cutting edge of progress; only gradually did the public come to view it as a "leper colony."

The buildings are very narrow and extremely long, facing due south to maximize sunlight. The upper floors are equipped with balconies. This is typical of 1930s heliotropic architecture, designed to harness fresh air and the restorative virtues of the sun. Consequently, the buildings are only 4 meters wide but nearly a kilometer long. The rooms are three meters wide and the corridors one meter. Today, this presents challenges for renovation projects, as medical staff are forced to walk back and forth constantly. As a result, the building is not optimized for modern use, even if the original intent—prioritizing sun exposure—was the core of the project.

Under a faint winter sun, as wild boars flee in the distance, we shall now explore the premises.