Urban Exploration - The Sunshine Hospital

This documentary focuses on the abandoned hospital of Montigny-Le-Tilleul, called Le Rayon de Soleil (The Sunbeam). To be immediately clear on the matter, I specify upfront: the ground floor, the +1, and the +2 are under alarm. The ground floor is entirely covered. The junctions to the upper floors are closed off with metal fire doors, with padlocks and chains on all handles. The staircases are alarmed, the corridors of +1 and +2 are covered. Only floors 3 to 9 are not alarmed due to broken windows and pigeons. Regarding accessibility via the hospital, the connecting corridor has a badge-access door, then again a steel door with chain and padlock. The security service is at the rear. They have a 4-minute walk to catch you. Forget about an illegal visit.

To be honest, if people had been discreet and respectful, the security guards wouldn't have taken these hostile and radical measures. But as usual, the riff-raff broke everything and, on top of that, set fires. In short, it's also worth noting that Vesale hospital is adjacent, you see? A functioning hospital. The manager got scared of so many excesses, which is understandable.

Since then, and ultimately, the practice of urbex consists of using blowtorches to cut through the metal sheets blocking the ground floor and first floor, setting off the alarms, realizing the junctions are closed, and getting caught. Le Rayon de Soleil is a heavy burden for the ISPPC to manage.

This documentary provides an update on the Le Rayon de Soleil site, a mythical place due to the colossal amount of bad luck that has followed it. It establishes the state of affairs as of late 2018, trying to avoid rumors, as false information spread by the press is legion.

History

Le Rayon de Soleil is a hospital created by the IOS, the Intercommunal Social Works. The IOS was established in 1937 under the direction of René De Cooman. The cooperative society intended to provide the Charleroi region with what it fundamentally lacked at the time: an ambitious social policy. Consequently, institutions sprang up (many of which are still present today): the Queen Astrid Maternity Hospital in 1937, the Cité de l'Enfance in Marcinelle in 1938, the L'Espérance home in De Haan Le Coq in 1940, the retirement homes in Courcelles in 1956, and in Farciennes in 1963. The policy pursued was very ambitious, particularly in gerontology and pediatrics. In this momentum, the hospital named Le Rayon de Soleil was built at the very beginning of 1954. However, due to not insignificant financial difficulties, the site was not inaugurated, hold on tight, until 1967. First major setback for Le Rayon de Soleil.

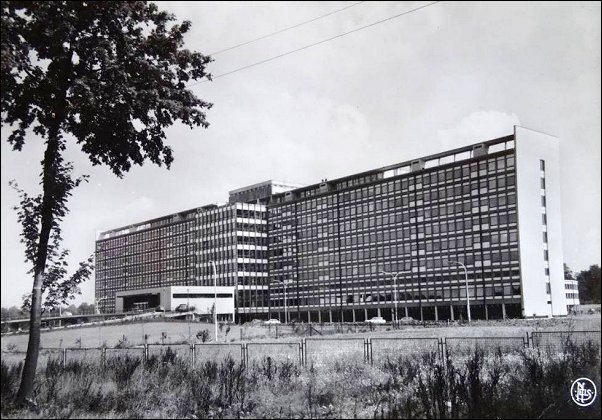

The construction was grandiose to say the least. The site covers 35,000 square meters, with a central column, two huge lateral wings, 9 floors plus the ground floor, a vast rotunda. It's to the point that the specific shape of the establishment became the IOS logo. The site's specialization was rehabilitation for chronic illness, combined primarily with geriatrics.

The establishment was specifically luxurious, or at least, no, that's not the right term: it offered optimal quality stay conditions. The restaurant was based on vegetables from the garden, cultivated on-site; the site had its own bakery, its own butcher shop. Part of the staff was housed on-site, in the 5 towers located to the west of Rue des Pinsons to this day. Some staff came from the Philippines; René De Cooman went to fetch them himself, which is why even today, in the vocabulary of the elders who knew all this, the site is called "the Philippines." A rumor still persists that dogs were consumed there!

The hospital was divided into several sections. L'Oasis was the geriatric unit, La Quiétude the long-term illness unit, Les Bambis the nursery, which was originally intended for the children of female staff. Through successive commissioning, the establishment reached a capacity of 1500 beds. In 1973, a center for the study of aging was added to the site, which also explains the presence of an amphitheater at the heart of the Rotunda. This amphitheater was used for a time as a studio by RTBF Charleroi; it's where the entertainment show "Bon Week-end" was filmed.

However, once again, the site seems cursed. Indeed, the "Pays Noir" (Black Country, referring to the Charleroi industrial region) found itself with a very high overcapacity in hospital units. From the late 70s, intense financial difficulties occurred. The situation becoming alarming, public authorities got involved. In 1982, orders were given to reduce the reception capacity as finances plunged into the red. Despite significant austerity measures, the situation worsened so much that in 1985, it was decided to proceed with the outright closure of the establishment. At that date, 300 people were laid off. The hospital had only operated for 18 years, and even then, far from full capacity. Only the eastern part, with 500 beds, was preserved, which is the current Vesale establishment, still in operation. So, we are at that pivotal moment when the doors closed.

A Collection of Setbacks

In 1988, the hospital was sold to an Italian real estate company from Abruzzo for 5 million euros. Only problem, and it's not a small one: the company is fictitious, or at the very least, very obscure. The fictitious goal was to install a hotel infrastructure and a shopping center. The financial operation that took place was nothing less than a vast scam, plunging the institution into a gigantic administrative and judicial mess.

Moreover, a misappropriation of 200,000 euros (today, at the time it was in francs) was carried out. The misappropriation in question stems from a shady affair orchestrated by a con man, Richard Carlier, a huge repeat offender, who was a PS (Socialist Party) boss and also director of the IOS. This wheeler-dealer greatly contributed to the deplorable image of Charleroi and the equally degraded image of the PS. This baron of shady dealings held up to 50 paid positions and established a vast corruption network. Sentenced to prison, he served a short sentence, then expatriated to Spain to flee Carolo (Charleroi) justice.

The problem, beyond this misappropriation, is that the court ruled that despite the fraud, the aforementioned Italian company is still the owner of the site. Until a judgment rendered in 2018, and yes, I'm talking about 2018!, the building still belonged to this fictitious company. The fictitious sale of Le Rayon de Soleil was annulled by the justice system 29 years later (find the error). Consequently, nothing could be done with Le Rayon de Soleil. Ownership reverted to the ISPPC, the victim of this plundering orchestrated by a PS henchman, on January 26, 2018. Finally!!

This situation was profoundly aggravated by the 1991 documentary by Jean-Claude Defossé on useless large-scale projects. The building became at that moment the symbol of Carolo waste and shady dealings. Although we understand the journalistic purpose of this television documentary, it further sank the site, which from that date acquired the status of a mythical place. The IOS was robbed by its director, justice did more than drag its feet, it inerted the file, and then, 30 years of abandonment ensued. Vesale hospital had to survive at all costs in this deleterious atmosphere.

From 2016 onwards, the ISPPC formed projects, but given the dreadful slowness of justice, it still struggled with the cumbersome mammoth, which geographically has since then served as the welcoming committee for Vesale.

Nowadays, we hear a lot of things, but apparently, the decision has been made to demolish the building, which, as the cherry on top, is full of asbestos. The construction site will not be easy. The main project would be to create a retirement home, all within a green setting. Only the future will tell us if this materializes.

In the immediate term, Vesale sells and gives away. The hospital's contents have been deeply destructured; not much remains that is legible compared to Defossé's pseudo-state of affairs. The ISPPC sent medical equipment to Sudan, and furniture to the municipality of Merbes-Le-Château. Fortunately, not everything is lost, even though vandalism has been brutal.

Amid more or less incessant degradation, a fire occurred in 2017. Gradually, everyone began to dream that the building would be razed. Understandably. Unlike the Queen Astrid Maternity Hospital, here no one will have any regrets.

René De Cooman, the IOS Epic

The history of Le Rayon de Soleil resembles an eclipse: a short burst of light then a long disappearance into darkness. It's an existence filled with much darkness, sadness, waste, and uselessness. Ultimately, this fall overshadows the journey of the IOS, which was remarkable. Progress on the social front was enormous, something the ISPPC is now the heir and guarantor of. If one work captures that of the IOS well, it's Jacques Guyaux's: *René De Cooman, the Builder of Social Works*. Unfortunately, it is perfectly unfindable.

René De Cooman is the man who created this whole system, and if he is mainly remembered for the Queen Astrid Maternity Hospital, the number of establishments he implemented is impressive. Not just the number, since it was above all a system of human protection that he set up during his life of dedication. A book would be needed to discuss the substance of this great benevolence. It is in this spirit that I nonetheless wish to partly erase this aspect of darkness concerning Le Rayon de Soleil. It was the last social work of this benefactor. Certainly, it fell like a phoenix in fire from the sky and is not reborn from its ashes. Let's keep in mind that in the Pays Noir, De Cooman's work (precisely very ignored and undervalued) was precious.

In this spirit, we quote here a part of the inauguration speech of Le Rayon de Soleil. This text gives some snippets of the reasons that led to the construction of the "liner." One could consider this load of text as tedious, but it proves indispensable. Talking about the wasteland without evoking its *raison d'être* is to focus on the darkness.

Here is the text:

"In 1954, a 30-hectare plot was acquired in Montigny-le-Tilleul. On August 17, René De Cooman launched this appeal: For nine years, we have been welcoming the elderly at Miaucourt. Some of them have become senile, and we cannot consider getting rid of them. However, what a handicap for the proper functioning of our 'Heureux Séjour' and also what a lamentable spectacle for our other residents whose morale must suffer at the thought that such a fate could be theirs. On the other hand, Public Assistance Commissions complain, with seemingly valid reason, that we only accept their able-bodied elderly and that they find it almost impossible to place their infirm. The latter generally end up in one hospital or another where they occupy a certain number of beds, which are so desperately needed in hospitals. All statistics prove that there is a staggering shortage of beds, and if, despite this shortage, the infirm must still immobilize a certain number, the problem is even more serious.

Therefore, it is urgently necessary to create a specialized institution to receive all these cases that do not belong in a hospital. But this institution must not only house infirm elderly or those suffering from mental or vascular senility. To admit only elderly whose days are numbered or condemned tuberculosis patients who must leave the sanatorium and return to their families, at the risk of contaminating them, would be a grave mistake, as the establishment's reputation would quickly be made. Knowing that one enters there to die, after a few years it would have to close for lack of clientele. It is therefore appropriate to research which other categories of patients could benefit from the new work. These are those who would be led to stay there for a more or less long period with the possibility of partially recovering their faculties. The Centre, which would once again receive the symbolic and optimistic name of 'Rayon de Soleil,' would welcome patients from three categories: 1) the socially active and recoverable; 2) the socially active but irrecoverable, at the current stage of medical science (cancer patients, notably); 3) the socially inactive (elderly), recoverable and irrecoverable.

When, on October 21, 1967, the 'Rayon de Soleil' was inaugurated, Doctor Halter summarized, in excellent phrases, the reasons that had dictated its necessity: In the aftermath of the last war, at the moment when the indispensable reform of the Belgian hospital network was beginning, a new concern appeared with a certain acuity: that of providing the elderly and chronic patients with the care their condition required and which the community had hardly felt until then.

Certainly, for a long time, the accommodation, I would even say rather the segregation of the elderly, took place within the community in 'hospices' whose very name has left, in the minds of many, a justifiably pejorative resonance. The notion of indigence on the one hand, and charity on the other, led to solutions that generally constituted, for the 'beneficiaries,' the entry into the antechamber of death. Promiscuity in enormous dormitories, separation of spouses, absence of appropriate care were the rule. The awareness of the problem of population aging sparked an important movement of humanization in favor of the elderly. The Intercommunal Social Works of the Charleroi region, under the impetus of its president, Deputy René De Cooman, was one of the first to resolutely engage in this direction. The cités of Courcelles and Farciennes are shining testimonies to this. But decently and humanely housing the elderly could not suffice, and the sight of the serious infirmities brought by age could not leave the Intercommunal indifferent. Barely completed, the Queen Astrid Maternity Hospital and the Cité de l'Enfance, which constituted the most urgent problems, René De Cooman embarked on the search for a solution to the problem of housing the elderly and, above all, to that of the care to give them. I had the favor, from 1952 onwards, of being associated with these concerns seeking their solution.

As a technician in charge of implementing the hospital reform, I had been able, for my part, to observe the disappointing fate that hospitals reserved for chronic patients and sick elderly. The Department of Public Health had, for its part, resolutely laid the foundations for the reform of retirement homes and also sought its way in the complex problem of treating chronic diseases that populated acute care hospitals.

Not only was the number of these patients large, but also the capacity of treatments that should have been applied to them made the most audacious recoil. However, the President of the Intercommunal did not recoil and deliberately undertook the study of the problem.

From 1952 to 1955, efforts were made to specify the nature of the problem and its solutions. Among the difficulties encountered were medical questions related to the definition of cases that could benefit from active treatments, moral and psychological questions relating to the consequences of gathering, in the same institution, a significant number of elderly people whose infirmities and illnesses risked hastening death, and finally, social and financial questions whose solution was indispensable before undertaking the adventure of a realization. Problem after problem, difficulty after difficulty, the president's tireless tenacity resolved them all.

Certainly, it took time, and it was hardly until 1960 that the cascade of decisions could be taken first by the Intercommunal, then by the Minister of Public Health, within the framework of a coherent program that henceforth aimed at all aspects of care for chronic patients. (...) These are the tasks that Le Rayon de Soleil took upon itself, leaving to other institutions the care of ensuring the long stays that cannot be avoided by those whom medical science is not able to relieve or improve.

Le Rayon de Soleil has 504 beds, always occupied, to the last one. In the final stage, it will have twice that, and it will not be too many. On November 21, 1970, the Oasis was inaugurated as an annex, a psychogeriatric center of 253 beds (also always occupied) intended for the mentally senile. Formerly, not so long ago, all these cases were irremediable; specially cared for, half of the seriously ill can now either return home or reintegrate into Le Rayon de Soleil because they are mentally rebalanced.

On the day of the inauguration, René De Cooman made two quotes. The first was from Doctor Diederich, the father of British Social Security: 'Social security must protect the human being from birth to death.' The second from Doctor Kessler, director of the West Orange Rehabilitation Center in Springfield, a former United Nations expert, specially versed in the diseases or infirmities of Veterans: 'Every human being can go three weeks without eating, three days without drinking, three minutes without breathing, but not a second without hope.' These are two formulas that, exemplarily, throughout his life as a stubborn fighter, builder, and benefactor, guided his effort."