Urban Exploration - The Safari Castle

We received photos from a traveler and compiled them into a historical summary.

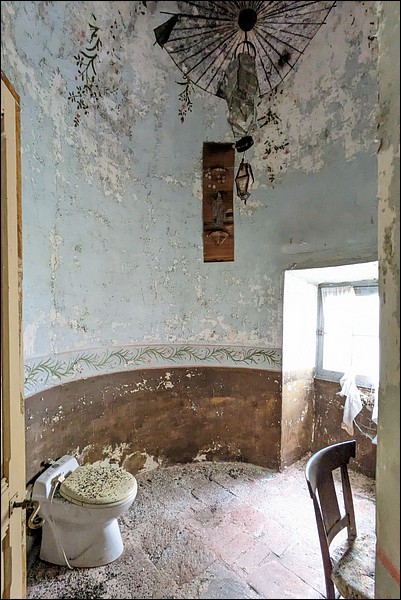

Embarking on this urbex mission is a journey. It is the story of a castle that could begin with "once upon a time," in a far-off era, when a family came to settle in this fortified house (bastide) lost in untouched nature. But far beyond that, it is a step aside into another time: a withdrawal, a seclusion, becoming crippled by silence to the point of inextricable pain. Once upon a time, then.

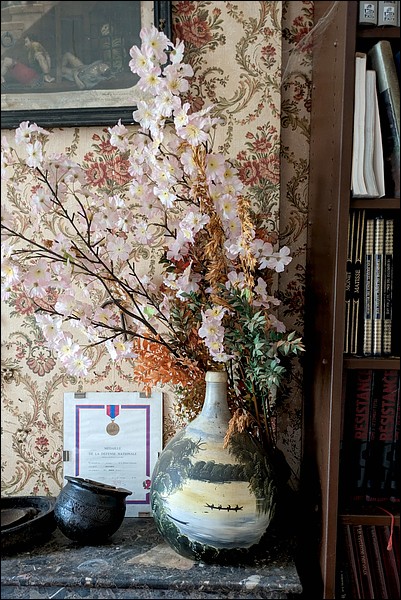

Pierre, who wore the red beret through his military career, left for Africa. He served in various countries: Gabon, Chad, Cameroon, and likely many others. He held a high rank in the Army. He passed away in 1939 and was buried in France.

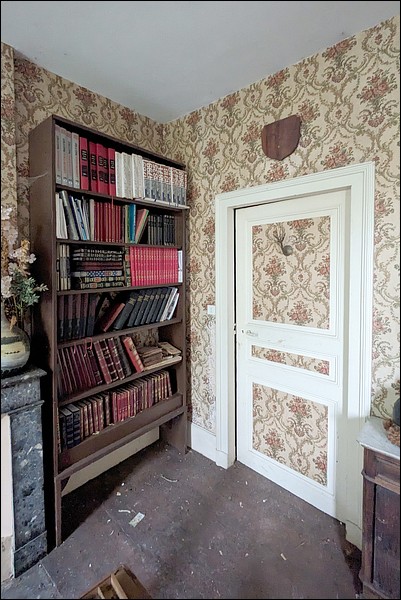

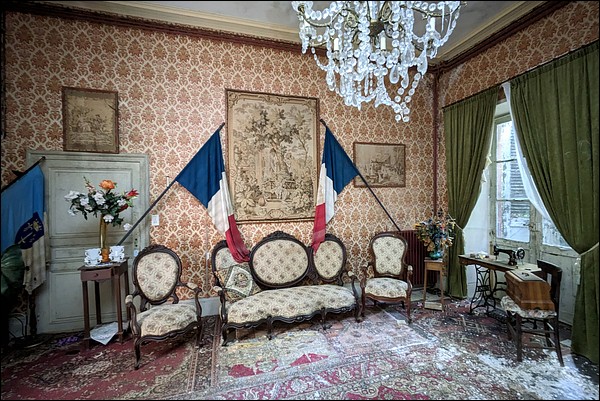

Up to this point, it is a fairly ordinary story, except that at the end of his career, wishing to retire, he purchased a castle—a hermitage in need of work. The structure has a haughty appearance, perched on a mound encircled by walls. One might venture a date: the original foundations date back to 1517. Transformed, it became a dreamlike sanctuary.

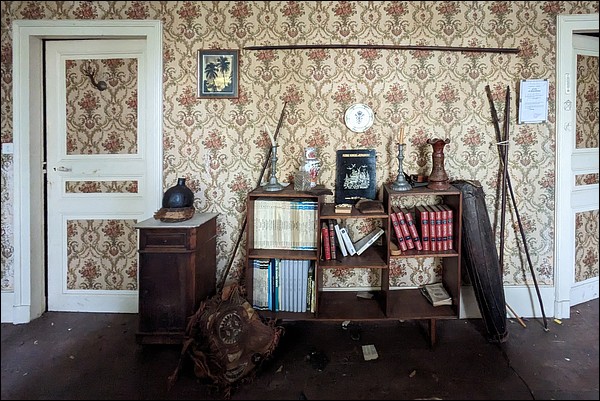

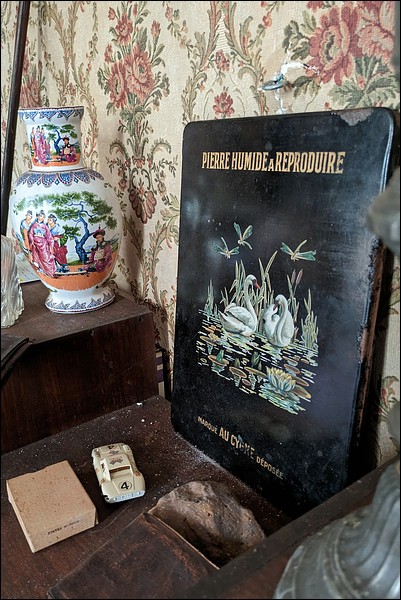

When coups occurred in highly unstable countries, Pierre would hide dignitaries or their children. In gratitude, he received a vast array of gifts.

It is a trail of clues that brought us here—lives almost vanished, much like the building drowned in the lush vegetation of a globally rainy summer. Every square inch of the parking area prompts a single question: why? For in this place, so calm in every direction, wherever one stands there is only a somewhat raspy cry… it is not particularly usual. Nor, perhaps, normal.

I have read exhausting accounts regarding the accessibility of this place—some taking hours to find it. It is true that nothing is a straight line anymore, just as the story has closed, a lid on the box of memories; it’s not so much that we no longer know, but rather that we no longer speak.

For it must be acknowledged: the meteorite, exhausted by grief, imploded in mid-flight. Today, nothing remains but a memory torn by pain. The forest path is easy, until the moment comes to veer toward the castle; there lies the gate of oblivion, marked by brambles and barred by impenetrable walls on slippery slopes.

It is extremely early when I arrive. For discretion? Not even. It is simply about taking time—for peace, for reflection, time also to understand them, to appreciate them. It is a form of love.

The castle is surprising, to say the least, because of its contents—an African inspiration gathering various cultures. Pierre received rewards because he put himself at risk to hide dignitaries during coups, as well as their children and relatives. Consequently, the living room resembled a museum of African culture.

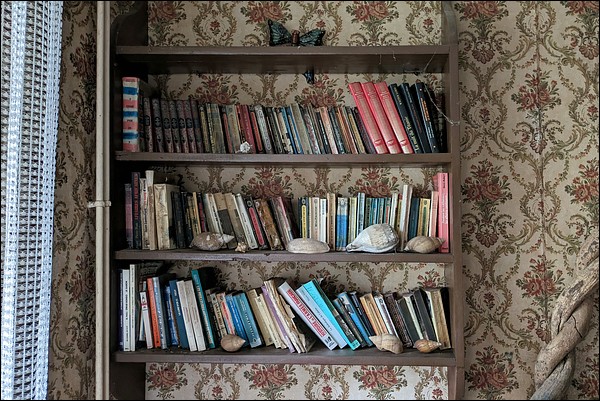

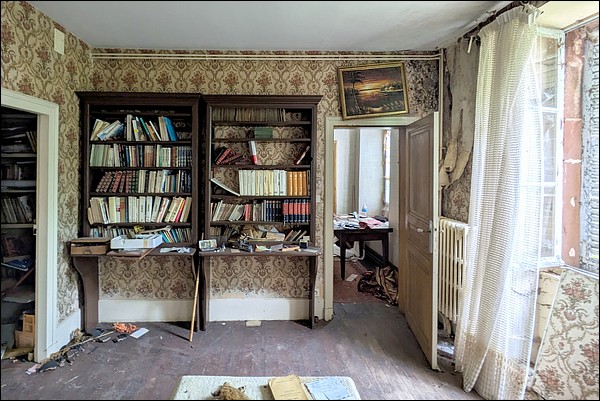

Pierre had a son named Georges, who likewise continued activities in Africa. Advancing in his career, he was tasked with strategic issues such as the construction of bridges to cross infernal waterways. It was perfectly logical that the castle was further filled with diverse African arts. Georges was eminently cultured; the library contains both geography books and works on the Resistance.

When one knows this castle almost perfectly through the photos of previous visitors, the description I must give is a massive disappointment. Every single object of monetary value has been stolen.

Where are the elephant tusks? Stolen. Where are the tortoise shells, the mace, the red beret? Stolen. Where is the leopard skin, the Dogon spears? Stolen. The masks, the statues, the paintings, the weapons, the ivories? And those are just the prominent items that come to mind. With every passing urbexer or other individuals, one could add another item to the list.

Depredation and vandalism have turned this place into a shadow of its former self. The last traces of occupation reportedly date back to 2011. If only it were the family who had taken the African relics; I naively dream that it wasn’t theft, but simply a preservation effort to keep them safe. I find it hard to believe. It is like killing Georges a second time—the raw reality of things.

When one leaves an urbex site desired for so long, there is a precise, quantifiable moment when you know you are leaving never to return—keeping only the preciousness of memories. You also know that the quest ahead, extremely uncertain, is to have the chance to find the grave. By chance, or by forcing chance: by desiring it. A trail of clues.

On the slippery slopes overgrown with spiteful sarsaparilla, I see myself carrying a gigantic elephant tusk. How could they do this? Why did they do it? There is such a black market; it is unsellable. It is so dangerous to possess such things without a family history to justify them. They have defiled it; there is no other word.

The farmer, immediately adjacent, acts as the caretaker and is distraught by such a relentless drive to pillage everything. The devastation of this castle is the most intense I have encountered in all my urbex journeys. And yet I am asked to be peaceful regarding the sharing of locations?

So, on the way back, as evening falls, my gaze fixed on a peaceful meadow—a jay has been fussing in the treeline for a while now—a lady, a local resident, approaches me (she is a bit afraid of intruding; she is so very welcome). I tell her, I tell us, that we will never know, but all that matters are the traces of love we left back there. For the others, perhaps. The next ones. I don’t know. I’m going to sleep here. I can stop by if I need water, she tells me. Anytime.

I certainly won't leave a tin of saka-saka on the grave. Perhaps a calabash shell filled with small stones: one for every day I thought of them.