The Castle of Largentière

This documentary explores the Château de Largentière, located in the Ardèche region. You will notice the significant state of disrepair in certain areas. This is precisely why this documentary was made. In fact, in the week following this report, the château underwent a complete renovation, initially for an archaeological dig, followed by restoration work.

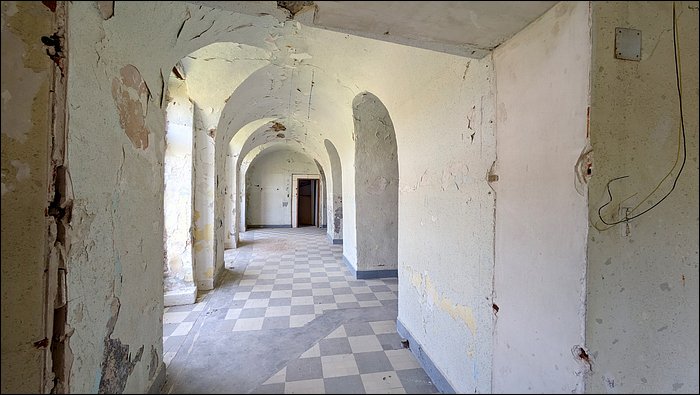

We felt it was important to preserve a record of the site, to capture at the last minute an image of what it once was, before the extensive restoration work began. It is true that—we wager—few, if any, residents of Largentière suspect that it is so vast, on the one hand, and so dilapidated, on the other.

The documentary was directed by the Largentière town hall, Mr. André Paul and Mr. Alban Guillemin, and carried out with the support of Christiane Fargier. We thank them for taking so much to heart the idea of ??protecting heritage by creating an inventory through images; this is rare enough to be worth mentioning.

Introduction, a documentary that proved indispensable

The Château de Largentière boasts a rich history spanning over eight centuries, intimately linked to the exploitation of the medieval silver-lead mines that gave the town its name. This medieval fortress has weathered different eras, evolving with political, social, and economic transformations.

The Château de Largentière dominates the eponymous medieval town, as does the courthouse, and indeed, the massive tower of the Château de Montréal. No visitor can ignore these imposing sentinels. Given the signs indicating the château, via a street leading to a very discreet, closed metal gate (or even a gate that could be described as anonymous, one must be in the know), most would assume that the site is open to tourists.

Beautiful from the outside, no one suspects the intense deterioration within; nor is anyone aware of the significant cracks located on the upper parts of the château. In reality, perched atop an enormous rock, everything quickly becomes "height" with this building. As a result, it's discreet, almost hidden, almost too hidden: people don't know about it.

Its rich and complex history reflects the power dynamics and economic stakes that have shaped the Vivarais region over the centuries. The very existence of the town and its castle is inextricably linked to the presence of countless silver deposits, a source of covetousness and conflict since the Middle Ages. From a feudal fortress to an aristocratic residence, then from an instrument of the revolutionary state to a public hospital, the building has constantly evolved according to the needs of its time.

This report aims to establish a complete and detailed history of this turbulent, almost chaotic, heritage by analyzing its architectural evolution, its successive owners, and how each transformation reflects a chapter of local history.

Originally, the rivalry was for silver mines (12th - 13th centuries)

The history of Largentière Castle is rooted in the strategic importance of silver mines. In the 10th century, the scarcity of gold in the West spurred the search for silver mines for the purpose of coin production, with the denier becoming the basic currency. It was in this context that the silver-bearing lead mines of the Ligne Valley, the main one being Baume de Viviers, acquired immense value. The first mention of Largentière, then known as the castrum of Ségalières, dates back to a 9th or 10th-century document, but the true history of the castle begins with the intensification of feudal conflicts over control of the deposits.

The ownership and exploitation of these mines became the source of a long and bitter dispute between two of the region's greatest powers: the bishops of Viviers and the counts of Toulouse. To assert their claims, each side strengthened its position. In 1146, the Holy Roman Emperor Conrad III granted William, Bishop of Viviers, the right to mint coins, thus legitimizing his authority over the resource. In response, Raymond V, Count of Toulouse, attempted to seize the mines, but an initial agreement was reached in 1193, followed by a second in 1198. This 1198 agreement divided the fortified settlement of Ségalières between the Count of Toulouse and the Bishop of Viviers.

This joint lordship explains the castle's unique initial structure. The building was not the result of a single, planned construction, but rather an agglomeration of independent fortifications, erected by different powers to assert their respective responsibilities.

The "Silver Tower," whose existence is documented as early as 1210 by an agreement between the Bishop and the Count of Toulouse, was the first cornerstone of what would become the keep. Meanwhile, the Count of Toulouse had a second tower built to the south of the first, of which only the semi-circular base remains today. Around the same time, two other co-lords, Adhémar of Poitiers and Bermond of Anduze, who had received a share of the bishop's fiefdom, erected two round towers to the east to protect the entrance to the castle enclosure. The Château de Largentière was therefore not a monolithic fortress, but a patchwork of stones, whose fragmented architecture directly reflected the fragmentation of power and the ongoing tensions surrounding control of mineral wealth.

The conflict ended after the Albigensian Crusade, which brought the County of Toulouse under the rule of the King of France. Following the defeat of the counts, the Bishop of Viviers remained the sole owner of the mines and the castle complex, consolidating his authority over the entire site.

The great episcopal construction project, from the fragmented fortress to the single castle (14th - 16th centuries)

The consolidation of episcopal power over the mines and the fortress laid the foundations for a major architectural transformation. Although the agreements of 1306 annexed the episcopal lands of Vivarais to the French crown, the bishop's power over mining operations and the castle remained intact. It was at the end of the 15th century that Bishops Jean de Montchenu and Claude de Tournon embarked on a monumental architectural program. An expansion project was launched.

This phase of construction was more than a simple reinforcement of defenses. It was a symbolic act of power. The Château Neuf, as it was named, completely absorbed the pre-existing structure. The bishops incorporated the two twin towers erected by the former co-lords into the new fortified enclosure. They built a wing, nicknamed the Pentagonal Tower, which connected these towers to the keep.

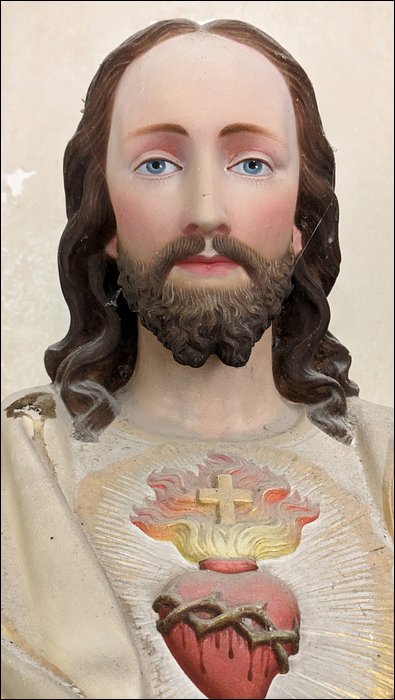

The castle's autonomy was further strengthened by the digging of a well allowing access to the river level. This well has been studied by archaeologists. It is approximately 50 meters deep and reaches the level of the Ligne River. It is accessible via a discreet trapdoor, 20 centimeters wide. This trapdoor is located near the old threshing machine, a piece of furniture that was inevitably removed, and more precisely in the corner of the corridor containing the marble slab commemorating the hospital's benefactors.

By creating a single, coherent structure from a series of independent towers, they erased the architectural traces of the former co-lordship and asserted their undisputed authority. The castle now appears as a homogeneous whole, a single fortress serving a single lord. The keep itself is characterized by Romanesque architecture, with walls 3 meters thick and access from the first floor, while the upper floors were connected by a spiral staircase within the thickness of the wall.

After a long period of abandonment following the religious wars, the castle was only sporadically occupied by Protestants during these conflicts, then by a royal garrison of about thirty men.

From the castle's seat to its transformation into a state room (17th - 18th centuries)

In the 17th century, the Château de Largentière continued to play a defensive role, exemplified by its resistance to a two-month siege during the Roure Revolt in 1670. However, the site's strategic importance gradually declined as the Vivarais region became integrated into the Kingdom of France. This transformation was formalized on November 5, 1716, when Bishop Martin de Ratabon sold the château and the barony of Largentière to the Marquis de Brison. Another source places the purchase by Marquis François de Beauvoir du Roure de Brison in 1730, but the date of 1716 is the most commonly cited.

The purchase of the château from the Bishops of Viviers was completed for the sum of 144,000 livres. The bishops used this considerable sum to build their new episcopal palace, which would later become the current Viviers Town Hall.

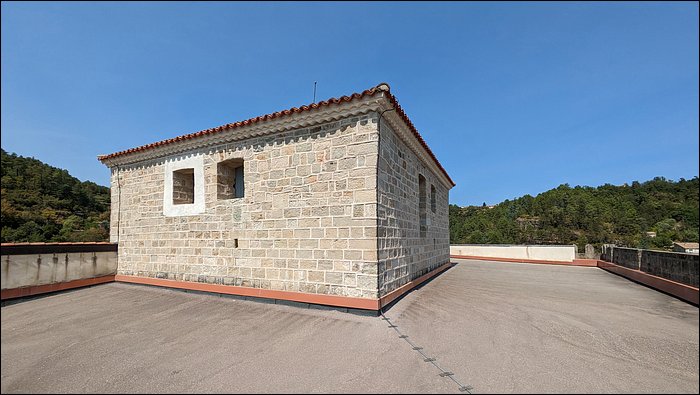

The sale of the château to the Du Roure de Brison family and its subsequent transformation marked a significant change. The château was no longer a military stronghold serving an economic or political power, but a lordly residence. The Marquis undertook extensive renovations to adapt the fortress to the housing standards of the time. He added large windows to the main façade, terraces, and transformed the lower enclosure into a raised platform with a monumental double staircase.

The moats were filled in, and a terrace was created. It is worth noting that to this day, these remaining open spaces, some of which have been filled in, serve as a drinking water reservoir for the entire town of Largentière. This water tower situation raises questions—or at least prompts reflection—regarding future public access to the château's gardens.

The military character gave way to pleasure and representation, an evolution that reflects the shift from a warlike nobility to a courtly nobility, and the loss of the building's original strategic function. The marquis died in 1734.

The castle tested by the Revolution and the 19th century

The French Revolution marked a radical break in the château's history. Considered the property of an émigré, the Marquis de Brison, the building was confiscated by the revolutionary committee of Largentière in 1792. The château was then repurposed for new public functions, housing the courthouse, prisons, and gendarmerie.

The chronology of this post-revolutionary period is sometimes a source of confusion among the available documentation. One document mentions an acquisition by the town in 1747 to be used as a hospital, a clearly erroneous date that does not correspond with any other source. The most reliable and well-documented sequence is as follows: under the Consulate, the unsold property of émigrés was returned to their families, and the Du Roure de Brison family recovered their château around 1802. However, the building did not immediately become a residence again. It was leased to the department to serve as a courthouse and prison, a use that continued until the construction of a new courthouse, inaugurated in 1847.

It was at this time that the town of Largentière acquired the building, either in 1845 or 1847, to convert it into a hospital and hospice. The château then began its longest period of public service. This transformation is a striking example of the Functional Democratization of aristocratic property. The building, once a stronghold of lords and a symbol of the power of an elite, became an instrument of the state, then a public service dedicated to the well-being of the community: a hospital. To adapt to this new function, the château underwent significant architectural modifications. The Toulouse Tower was demolished in 1816, and its stones were reused for a factory. New floors and a roof were added, completely concealing the keep from view.

The 20th and 21st centuries: between heritage, oblivion and rebirth

The castle served as a hospital and hospice for nearly 149 years, until its use ended in 1996. This extended period left its mark on the building, with the addition of annexes and concrete balconies that partially disfigured the southwest façade.

Today, the monument is weatherproof thanks to extensive restoration work carried out solely by the town council. However, it remains unoccupied and uninhabitable due to significant deterioration, inappropriate alterations made by the hospital, and unstable sections.

Despite these changes, the historical importance of the site was recognized by its listing as a historical monument by a decree of May 31, 1927. Following its decommissioning, several phases of restoration were undertaken. Volunteer work took place between 1997 and 1998, followed by a more ambitious campaign between 2013 and 2015 that led to the demolition of the concrete balconies and the restoration of the keep's roof, making it visible from the outside once again.

André Paul recalls: "There was a time when summer work camps at castles were very fashionable. The local council at the time called in teenagers: they removed plaster to expose the ancient stones; this was an attempt to erase unsightly alterations from the 1960s or similar periods. This type of work camp was a disaster—albeit well-intentioned—because many archaeological traces were irretrievably destroyed. These projects were not carried out according to best practices."

Today, in August 2025, the date of our visit, the castle is at the heart of a rehabilitation project: its transformation into a "Campus for Hospitality, Catering, and Tourism Professions." This project aims to revitalize the town center by creating a permanent training center for young people and professionals, a venue for seminars and events, and a hub for cultural activities. This initiative extends a tradition of hospitality training already existing in the town.

This repurposing brings the castle's history full circle. Built to protect the local economy from the silver mines, it is now being repurposed to serve the modern tourism industry. The site that once guarded the main source of wealth in the Middle Ages is being transformed into a training center for Largentière's new wealth, reinventing its function to serve the region.

2025, a pivotal year in the turbulent history of the castle

The municipality has determined that if no major restoration work is undertaken, the castle will collapse. This grim assessment is not an exaggeration. Cracks run the entire length of the ground on some of the facades (particularly the east side). Some cracks are 5 centimeters wide, which we filmed for documentary purposes.

The cost of this project far exceeds the budget of a town hall, including any planned tourism project. Therefore, in order to carry out a thorough renovation, essential to prevent the building's demise, it has been handed over to the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region.

The work will involve removing all the castle's contents, followed by an archaeological survey that will include the removal of all plasterwork, Placoplatre, and any inappropriate modern additions. Following this, a consolidation project will be undertaken, including structural reinforcement and a complete restoration of the building. As of 2025, the construction project is scheduled to last two years with a budget of €10.5 million.

In this documentary, we invite you to visit the castle. It has four levels. A small cellar level, where the castle's foundation on the rock is visible. A very large ground floor level, which includes a chapel. A very large first floor level, featuring arches. A second floor level, corresponding to the top of the keep.

We do not include the very small basement level, which is of no particular interest, nor the underground passage located beneath the castle at the level of the railway line.