The Penicillium underground mine

Here is a tour of an underground quarry where sand was mined. In a relatively distant time when the internet did not exist, we claimed that there were only three underground quarries in France that mined this type of material, in Vaucluse, Seine-et-Marne, and Béthune. Nothing could be further from the truth. There was a plethora of underground silica quarries, as the demand for glass was so pressing.

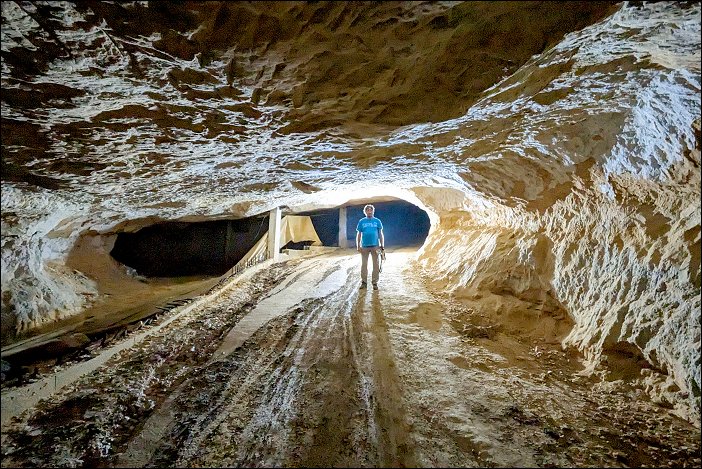

The underground site we are visiting has a bifurcated appearance, which is evident throughout the tour. The first point of view: a large underground operation, which could be described—although it is not easy—as a complicated rectangle measuring one kilometer by two. The second viewpoint: a mushroom farm and its growing rooms. The two aspects are so intertwined that one rarely exists without the other.

The mine dates back to the Industrial Revolution, which comes as no surprise. It is therefore a recent technology. However, there was no large-scale mechanization. Given the friable nature of the surrounding rock, the operation was carried out using picks (or even just hoes), shovels, crowbars, and wheelbarrows. Why so rudimentary? As with the catiches of Lille, one might think that the vineyards were cultivated during the warm season and the bottles were made during the off-season.

According to the archives, activity began in 1846. In some places, a dismantled Decauville railway track can be seen. This may seem curious, given that the network is operated on a fairly steep, unchanging gradient. It is said that eight horses could be used for traction.

The surrounding rock varies. Sometimes very pure, compact, white, almost sandstone, the sand is similar in appearance to that found in Puiselet. However, this is rare. Most of the surrounding rock is rich in ochre, which gives it a very pleasant fawn color. When the sand was pure, transparent bottles were made; when the sand was impure, green glass was made. It should be noted that there was a demand for glass jars for capers.

To see this place as solely a bottle factory is a gross oversimplification and incorrect. Depending on the ochre content, very impure sand was used in tile making, mixed with clay. This gave the tiles a beautiful color. Ochre was also used to coat facades, purely as in Gargas and Roussillon, in keeping with the mining traditions of Vaucluse.

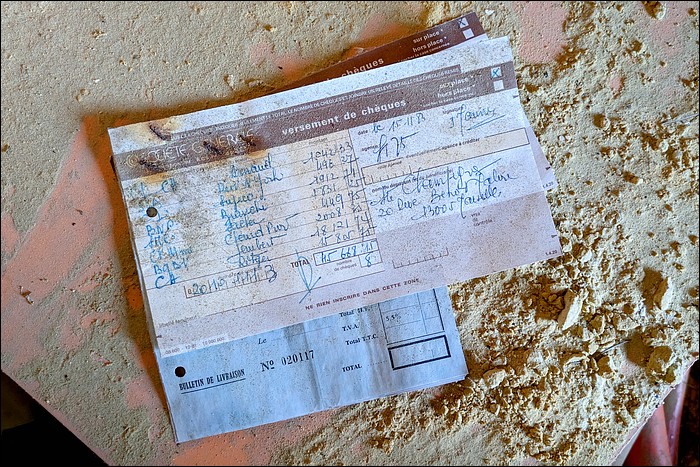

According to the archives, mining is thought to have ended in 1958. This remains relatively uncertain, as nothing in this place is clear-cut or black and white. It would be rather bold to say that mining was purely seasonal, just as the transition to mushroom cultivation was gradual.

It is fairly accurate to say that the mushroom farm dates back to the 1960s. However, the cultivation techniques were very archaic, with mushrooms grown on millstones rather than in bags or on tables. The stacks are still visible, although they have been heavily trampled or sometimes washed away by runoff during Mediterranean storms. In particular, we can see the remains of a large river that ends in an ocean of dried mud.

The mushroom farm has invariably partitioned the largest empty spaces into vast, very clean chambers. Cement pillars have been erected to support the ceiling. Some are slightly cracked, indicating that the underground world is slowly but surely disappearing; however, the whole complex is still in very good condition.

You can see a myriad of air vents, which were used to bring in fresh air. Air conditioning still exists near an old entrance. The walls were whitewashed, giving them a very white appearance, or copper-plated, which offers magnificent green hues.

The mushroom farm closed due to unfair competition from Poland when the European Community was established. The first galleries were used to store fireworks, and today the old tiles are occupied by a construction contractor. After a period of abandonment, the site is once again occupied.