The rice mill in Port-Saint-Louis-du-Rhône

We received photos from a traveler and compiled them into a historical summary.

We are in a dilapidated space. A place of destruction, like those found in vast, more or less abandoned industrial areas: whether we are talking about Hayange or Dunkirk, it looks the same. Here, it's a dirty party. A party with the sun, you might say. Everything is filthy, if not downright dirty. A child on a bike—a nice kid, by the way—throws firecrackers while dying of boredom. His eyes implore us to take him away, far away, somewhere else, anywhere but here.

Here we are on an urban exploration visit to the rice mill in Port-Saint-Louis-du-Rhône. The context is clear: the Wild West without panache, the flatlands without hope, linear to the point of gloom. We are here out of necessity, undoubtedly for work, the steel mill, the refinery, otherwise we would leave.

The rice mill in Port-Saint-Louis-du-Rhône is a monument to industrial heritage. It has a brutalist, Soviet, violent architecture. Large industrial cubes placed near an inlet or some other industrial feature, wedged into a former military wasteland. I name the place because the taggers have defaced absolutely everything; there is nothing left to protect.

The Port-Saint-Louis rice mill stands as a major industrial landmark in the Camargue region, its very presence evoking a rich and evolving past. The site is characterized by three huge buildings rising around an inner courtyard, creating an intimidating and impressive architecture that openly testifies to its former industrial power. Despite the ravages of time and the corrosive effects of the sea air, the building, with its vast cubes, remains impressive.

The rice mill was not an isolated entity, but an integral part of the deeply industrialized identity of Port-Saint-Louis. The city's economy was heavily dependent on its industrial port, with a substantial percentage of its salaried jobs linked to this sector. This context is crucial to understanding the scale and strategic positioning of the rice mill.

During the 1910s, France decided to revive rice cultivation in the Camargue, prompting the development of industrial processing facilities. Regularly, and this may seem surprising at first glance—we only have urbex sources, which casts doubt—the original purpose of the establishment was as a flour mill. Its conversion into a rice mill dates back to the 1930s. In addition to its long period of activity, which we will come back to later, in 2009, the rice mill ceased operations and fell into a state of abandonment.

The Camargue region, with its unique hydrological characteristics, has long been recognized as an ideal environment for rice cultivation. A significant turning point came in the 1910s, when France decided to revive this crop. This decision marked a political initiative motivated by food security concerns.

The process begins with cleaning the paddy rice to remove impurities such as stones and straw. Next comes husking, where the outer shell is removed to produce cargo rice or brown rice. The rice then undergoes milling, a crucial step that removes the germ and bran layer, usually with the help of abrasive machines. Finally, the grain is polished, often with micro-sprays of water, to achieve the desired smooth, white finish.

In many places, small piles of “husk,” the outer shell of the grain, can still be found. We have included a photo of this.

The industrial facility, due to its inevitable and constant evolution, can sometimes be confusing. Documents mention the Grand Moulin Gautier, the Moulin de Paris, and the Rizerie Uniriz. Paper documents refer to “the Franco-Indo-Chinese company.”

A surprising and crucial chapter in the history of the rice mill took place during World War II. The facility was occupied by the German navy, the Kriegsmarine. This transformation from an industrial processing plant to a military facility highlights its critical importance, probably due to its sturdy construction, large size, and strategic location near the mouth of the Rhône River.

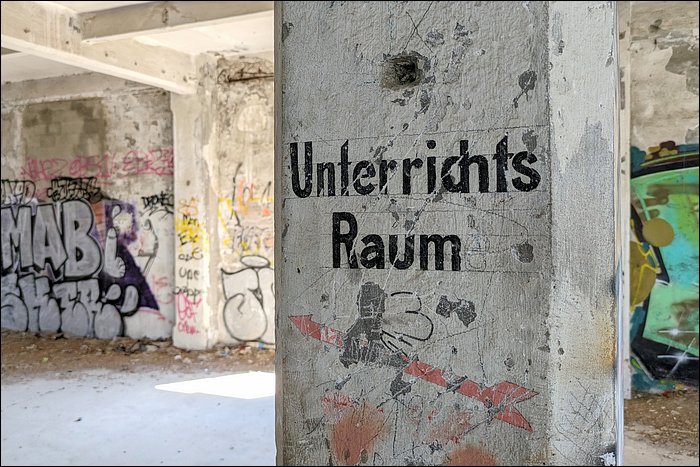

From this site, German forces orchestrated and developed defensive batteries along the coast. Tangible remnants of this period include German inscriptions on the walls and a painted staff map, providing direct physical evidence of its military occupation.

We note that the map was vandalized, completely destroyed, by the pseudo-artist Djalouz: https://djalouz.com/galerie/ We offer a big round of applause to this moron for destroying a historical relic when there is plenty of space everywhere else.

It is often mentioned in urbex documentaries that the tower at the top is a German observation post built to monitor the mouth of the Rhône. We believe this to be partially false. It was used opportunistically, nothing more. We note that the observation post has no roof. It could possibly have been a water tower. What's more, and more importantly, it has stars on it, which match the flag of Indochina at the time.

The occupation of the rice mill ended in August 1944, when it was liberated from German control. This event marked the return of the site to civilian hands. The rice mill ceased operations in 2009. Although the documents do not provide explicit reasons for this closure, several factors can be inferred. The aging infrastructure and the costs of maintenance or modernization probably played a role.

Today, we may be led to believe that the structure was bought by the municipality with a view to protecting one part or another. There is talk here and there of a project to protect the courtyard with its plane trees and the house that served as the administrative base. However, the damage is so extensive that it will take some creativity to do anything with it. To say that everything has been vandalized and polluted is an understatement; we are no longer even surprised by this.

Architecture of this Stalinist style remains rare overall, especially on this scale, and is well worth this documentary.