Unusual urban exploration - The Courouge Affair

To take an interest in industrial or mining heritage—or any heritage for that matter—is often to take an interest in the people behind it. Sometimes, heritage itself—in this case, a banal and insipid 16th-century house—fades away before the human legacy. This page is a tribute; not a glorious one, for that would be bland, but a sentimental one. Heritage belongs to architecture; the past of men to memory and feeling; the future to silence. For this reason, the house will not be located, and the people in the photographs (and the friends involved) will not be named. May they live in peace.

Plainly speaking—I would even say from a clinical perspective—it is an insipid abandoned house. A preservation order was attempted but failed, rejected by a regional authority. A wave of revolt rose from a local heritage association. Without wishing them direct harm, they missed something formidable: a human past with the substance of sea winds and squalls—a past impetuous with happiness, violent with misfortune. They clung to a gable wall that interests no one; they clung to a rotten staircase railing, crudely fashioned and missing pieces. In reality, they only looked at the stones. They did not open their eyes (though, strictly speaking, it was not their concern) to the heritage of the heart: the photographs, the letters of a woman with raw nerves, the torn memories on the floor.

Since the house itself is of no interest, its presentation is limited to thumbnails. One can skip looking at these images; they are only here for documentary purposes. At the request of several branches of the family, the letters were burned. On the advice of the absolute majority of the members of the Ugoc association, no content discovered from the 1995-2003 period will be revealed; the documents have now been cremated. All names of persons from the 1976-2006 period are kept secret out of discretion. Only documents from 1971-1976 are presented. These happy documents are simple.

One could honestly say it is filthy. Years of abandonment—four on the day of the visit—have accumulated many layers of disrespect: vandals, partygoers, squatters. That is without counting the wear of time, the rain, the winds, and even the animals, since we are in the open countryside, near the center of a hamlet whose name is of no importance. When, as a matter of conscience, I visited this house quickly one Monday at noon to assess if anything was worth photographing before its imminent demolition—out of concern for preserving architectural heritage—my car was badly parked. With feet like lead, I pulled out the camera only by reflex. No, there is nothing to protect. The so-called heritage argued by some is overrated, pathetic even; did they (did he) even go inside? The lightning visit ended in the attic. I was about to close the subject forever, not without being careful on the steps of the dilapidated staircase. It is dark and dusty; some floorboards hold only by magic. With the bitter—or should I say stinging, scratching, wounding—memory of a friend's near-accident, I mistrusted every rotten plank like a briar in a forest at night. That was when, with the tip of my foot, I pushed aside a jacket festering with vermin.

It is 6:20 AM the next morning. It is raining. Day is barely breaking at the end of a winter that refuses to finish; at least there is no melting snow, which is something. On the road, I crossed paths with almost no one. At this early hour, the world still belonged to me—not for long, I knew. When I parked the car at the farm near the enclosure, I thought of Céline, the student from the D. bakery who lived at No. 24. She probably laughed at my haggard face every Sunday morning when I went to get pastries; she even blushed once because, I imagine, she wanted to mock me but didn't dare. For a long time, she got up at 5:00 AM to go to work. This time, it was my turn to make the reverse journey—same time, same weather. At that precise moment, I imagined her having a coffee, and the vision soothed me. I walked along the muddy sidewalk. A few steps away were the heavy hoofprints of cows that had crossed the meadow. The earth is heavy with its glacial winter; it clings to your feet with cold hatred. I know what I am going to find, I know why, and I know how. Aside from a few details, I feel the weight of future revelations penetrating my flesh like thorns. The viscous fog slowly emerges from the nearby river; dawn is rising. The day will be both radiant and burdened by an immense weight of darkness; it would not be an exaggeration to speak of a vice of dust.

The house is exactly as it was the day before. This is hardly surprising. It is dead. A few shreds of torn lives lie moribund on the floor in an inextricable mess. The stairs creak under my steps. Its last moment of life, before dying under the humidity of its years of abandonment, will be to carry my footsteps, which in turn carry "her"—seven hundred and fifty "hers." The attic is even darker than the day before. To avoid the dust, which is terribly filthy, I put on gloves. With the lamp lit, what I saw yesterday is confirmed beyond any doubt. Under the attic boards are large, moderately rotten tie-beams. Clearing the boards—with no difficulty, as they are disintegrating—I find photo albums carefully hidden between the beams. Without looking at the contents yet, the search allows me to unearth four albums of various colors, a box of negatives, medium formats, and four boxes of slides. Other parts of the house contain heartbreaking letters from C., and school assignments from M. It is with a certain emotion that I carry down (thus leaving the living house for the last time) the box of albums with their warm, beating, precious—burning heart.

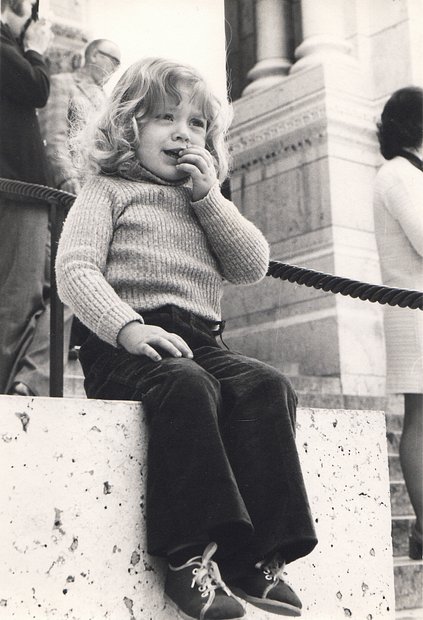

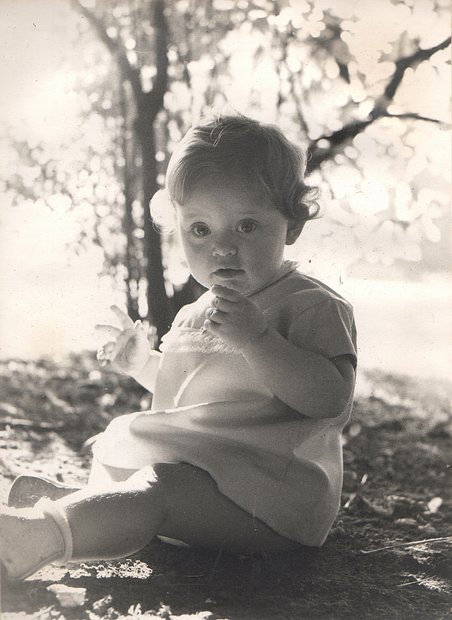

The entire day passed with unusual slowness. Unable to touch the treasure buried in the trunk of the car, I tried to focus my mind on not going back to the attic—with difficulty, my god, such difficulty... It took a good twelve hours of patience before I could unpack at home. The brush is ready, the restoration tools too. Since the Anderlues affair, this is a known process, almost banal. The photo albums reveal a series of 450 photographs, 200 slides, and 100 negatives. Except for two atypical images, the content is extremely consistent: it is the documentation of a little girl, an almost fanatical capturing of images, as if, for the love given, 750 images were not enough: photos, photos, photos, plenty, an immensity, a gigantism, a passion, a frenzy, a terrible and superb obsession of love. The images also hold another absolute, a more troubling one: they bear no name. None. None. None. Dates on a few slides frame the photographs bluntly: 1971–1976, not a centimeter more. No baby photos, no photos of the child as an older girl, teen, or adult. At that moment, I felt a gripping anxiety, like a rush of blood: what if this child were dead? What if the secret of the attic was a grave? I was very afraid. I admit it. My respect for people is great—or to tell the truth more accurately, I believe I should say that I wish it were so, without always succeeding. The specter of the "grave robber" followed me throughout the long days that followed. 488 days of investigation.

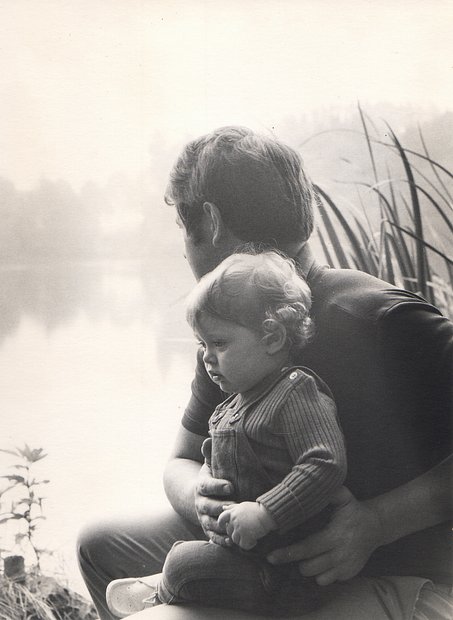

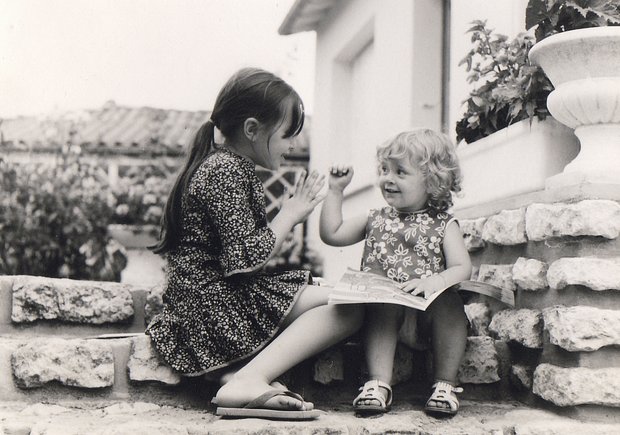

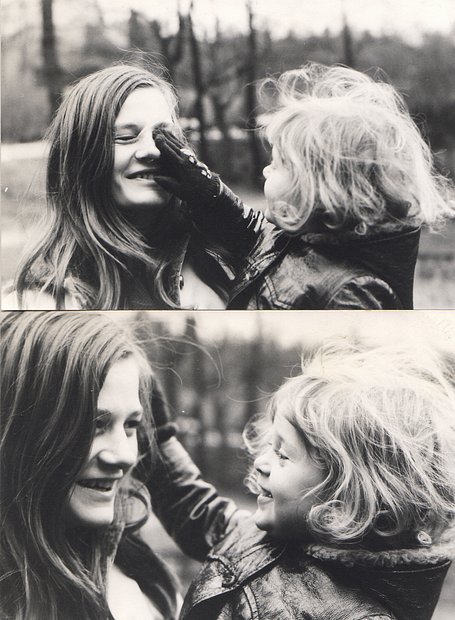

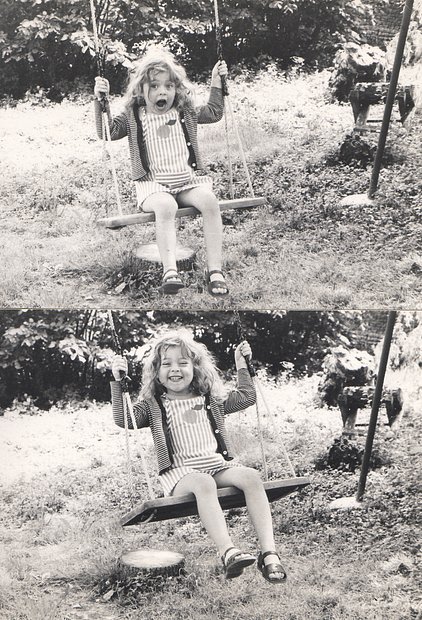

I believe the obsession that became mine, mirroring that of the photographer, was the stubbornness to put a name to the face. For this little girl—the child, as I often called her in dozens of phone calls—is sparkling with joy. How beautiful she is! She’s a little monster, and it’s touching. In some photos I don't show here, she clings to her father like a lifebuoy in a storm. In most of the images, she is a rascal. In these black and white photos, she is the shimmering mischief of life, the image of the dream child. Today, according to my suppositions, she is 41 years old. Who is she? How is she? Is it so foolish to fall in love with images of a luminous past hidden in a dark attic?

The investigation was long and strewn with many obstacles. There were mistakes. What a disappointment when Paul told me: "No, these photos aren't mine"—though I must say it would have surprised me. What a disappointment to receive no answer from Mélissa, no answer from Véronique (truthfully, even just the words "I am not the child" would have sufficed); what a disappointment not to find C., to know that her past is a deep gash much more painful than a scratch. For a long time, I remembered the quote Philippe wrote a while ago (attributed to Socrates): "If what you have to tell me is neither true, nor good, nor useful, I prefer not to know it, and as for you, I advise you to forget it."

Too true, it was. I understood it. At times, I even accepted it. But I believe I could never admit that the attic was the grave of this little one: the child. Even if I had to hear that she was dead, I would mourn her. Not as my own child. No, I would then watch the images burn, the faces blacken, with the sadness of losing someone I care about. An artificial feeling, superficial, probably false too, but yet very much there. Behind the heritage, there are humans; I have never been able to detach myself from this affection—too fast, too strong, a weakness of sorts: caring for strangers over trifles. The "sparkle" is the trifle. Probably. Because it is something we lack. Not all of us, but many. We adults have a sad life of obligation and a dull veil over our eyes that means we are no longer happy about anything. "If what you have to say is not good or useful?" I thought of Sophie Calle, whom Christie and I discovered a few years ago. A declaration of love to a photo from 1974—is that ultimately so useless? Even if a phone call were to distill venom into my veins: "She has been dead for twenty years." Even if I were to suffer for it. To make one's life a work of art—a small thought for Sophie Calle in passing—yes, it is useful. It might be nothing, but there it is, it sparkles, like the kid. So I gently advise myself not to forget; the night tries to convince me of it, with the moon as an earring.

The start of the night flies by in Saint-Gilles, Rue de Bosnie. I abandon M. in the memories, until I forget her first name. I just wish her good luck for the future and hope my childish prayer touches her. Later, my mind wanders to La Hulpe, Charleroi, then La Louvière. It would finally be the next day, on a forum, a completely innocuous message from a friend—the guy from the accident, actually—that would make me leap into the void. Coincidence. He, who knows nothing, happens to speak of the probable father, or almost—well, he doesn't realize it. Calling one more person was a requirement of courage. I was not comfortable. It was done. It was not easy. Nor was it pleasant. The discussion didn't bring much new, except that my nocturnal imaginings were well-founded. It earned me a mocking word from Sandy on a photo of me, by the way: "I'm going to put the date and full name, so when it's lost in an attic, you can be found more easily." A puzzle piece had just been added, giving a precious but insufficient clue: the first name of the child, the kid, the brat, the little rascal. But not the last name.

The Courouge affair would end in the suburbs of the night. The photographs are cleaned one by one, stored like a precious possession in a healthy, heated house. 34 years separate us from the last image. In 34 years, when I am—if I am lucky enough to get that far—an old man, I will receive a phone call. This call will stem from the same stubbornness that was mine for 488 days, from the same fury of love that possessed this photographer for at least 5 years. A distant voice will give me the name and the location of the grave. It will be far, but I will go. No one will know why anymore. Except me. In front of the grave, there will be a sign made by the municipal administration, informing that the plot is not being maintained and that the grave will be demolished. I will throw away the sign with a certain form of rage. And I will lay my flowers there. I will probably be angry at giving flowers to marble rather than to a living being—anyone, her brother, her son, who knows. But my gesture will never have been useless, no, never.

Close your eyes. Now. And imagine it is you. Right now. You are in the attic of an abandoned house. A cruel twist of fate makes you discover that photo albums are hidden in the debris of a floor. It is full of dust. The discovery belongs only to you and your secret. When you open it, you find this gold. What would your reaction be?

Epilogue: After yet another twist that upended all my constructed theories, the Courouge affair found its conclusion, the one so hoped for. The child in the photos is named Anne, or rather Nana. We met at the Parvis de Saint-Gilles on July 17, 2010. She got the albums back. It is a very long story to tell, and I believe it does not belong to the internet but simply to our memories.

The Courouge affair slowly closes, the secrets fade. We dug a 6-year-old girl out of the slats of a coffin to give her back to the light of day; it is the end of something for the beginning of something else. It is for life—in a way, a poignant tribute to existence—just like (as she says) those entire anonymous lives that are unpacked one morning at a flea market due to death or eviction. Sometimes there are images of the past that have more of a historical character than anything else, at least for us because it’s so long ago—I think of those letters from the 1914-1918 war—we feel less attached to them. Here, it is a banal but beautiful childhood tale, it is an Eden, vacations in the Marais Poitevin, it is you, it is us; we all find ourselves somewhere in it. It wasn't the photos that were important, but the gesture—the gesture of existing. Of having returned to life what did not deserve the eternal shadow of an attic too dirty for such beautiful memories. To the future of Ange-Félix and Diégo.

On March 8, 2011, very early in the morning—as if to perpetuate something that had become a tradition—an open letter was created for the residents. This long banner was based on a text slightly longer than the internet version, notably because the name of the village could now be revealed without issue. Though the content was mocked and then fell victim to vandalism, it was a necessity, one year later, to tell the neighbors what might have happened there, between those walls; because despite appearances, the dwelling still carried a fiber of life, however tiny. Here are a few images of that banner. Since it began to rain on it quite quickly, it was removed so as not to look messy. The house is now definitively dead.